In a prior article, we pushed back at some of the more aggressive predictions being made about the potential for Transport as a Service or "TaaS" to disrupt the existing vehicle industry. In a second article, we also made some observations about the current optimism regarding the speed at which Electric Vehicles (EV) may penetrate the traditional Internal Combustion Engine or "ICE" vehicle market. We pointed out that EV technology still needs to make significant progress before EVs are likely to be widely adopted.

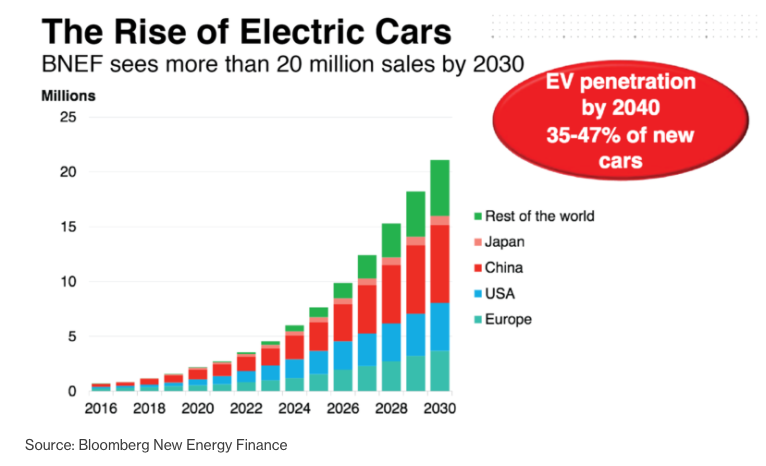

Nevertheless, we conceded that the market share of EVs is still likely to grow quite rapidly in the next decade. So, in this final article of our three part series, we consider the potential impact on energy markets and specifically the demand for oil (NYSEARCA:USO).

Even if TaaS does not fulfill some of the lofty expectations that now abound and individually-owned vehicles still account for a large proportion of the entire vehicle stock, many vehicle owners may still end up owning electric vehicles or EVs as opposed to ICE vehicles in the future. Thus, the outlook for oil demand in the next decade is still quite negative, regardless of whether TaaS proves to be a widespread success or not.

On the positive side however, we would also argue that oil demand will continue to grow for at least several more years even under the most optimistic scenarios for EV market penetration. At present, the total EV fleet is less than 0.5% of the total global vehicle fleet. Furthermore, the global vehicle fleet itself will probably continue to grow by around 3% per annum, being driven by still low levels of vehicle ownership in countries such as China and India.

Some back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that total oil demand is only likely to peak around 2024/2025, even if EV market penetration of the global vehicle stock reaches 50% by 2030. This is based on a level of 1% in 2019, which is optimistic considering the cost and infrastructure requirements in developing countries. Furthermore, one must remember that transportation does not account for 100% of global oil demand and that the petrochemical sector is also an important source of oil demand, accounting for roughly 15% of all consumption.

Assuming vastly improved fuel efficiency going forward, global oil demand is still likely to grow by around 1mn bpd or 1% per annum until at least 2023/2024, even under the most optimistic scenarios for EV market penetration. We also think this scenario has a low probability at present. Consider the fact that the most economical EVs to date, namely the Chevy (NYSE:GM) Bolt and the upcoming Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA) 3, will still cost around $35,000 per vehicle. Range is still limited to around 200 miles, half of that of conventional vehicles, and recharge times are around 30mins.

And range will remain an important consideration taking into account some 35% of all American households or 40mn take at least one annual long distance road-based vacation. A consumer can buy a BMW (OTCPK:BMWYY) 320i for the same price without the recharge hassle and double the range, or an entry level vehicle for half the price of the Bolt and the Tesla model 3. It thus becomes clear that further technological improvements will be required before mass adoption takes place.

Some point to the potential for a national network of "supercharger" infrastructure that can be deployed helping to overcome the range anxiety that consumers may have with regard to EVs. Indeed, this may help alleviate some of the concerns regarding the range limitations that EVs have, particularly if battery technology does not improve as fast as currently envisaged. However, current superchargers still take some 30min to recharge a Tesla EV, as opposed to 5 minutes for ICE vehicles.

So intuitively, in order to facilitate the same capacity utilization as the current national gasoline network, one would in theory need many more supercharger stations than gasoline stations. Nationally, in the United States, there are some 120,000 gasoline stations currently as opposed to roughly 400 supercharger stations. At between $300,000 and $400,000 to build one supercharger station, a network of 120,000 supercharger stations would cost around $40bn.

Naturally, many will point out that the supercharger network only exists to cater for long-distance driving and that most EV owners will recharge their vehicles at home overnight. This is assuming they have the ability to recharge their vehicles at home. Nevertheless, many Americans will still take a number of long distance trips per year even excluding trips taken purely for leisure or vacation.

The latest data from the Bureau of Transportation Statistics suggests total annual long-distance mileage (defined as greater than 100 miles) is roughly 760bn miles or 2bn per day. At an average recharge distance of 200 miles and assuming each supercharger can deliver 24 charges per day, we are still looking at around 420,000 superchargers or 70,000 stations assuming 6 supercharger points per station. This would still entail a total cost of around $21bn.

However, for the sake of completeness, we will assume that the optimistic scenario for EVs reaching a market share of 50% by 2030 to be accurate. In this scenario, global oil consumption will still rise from about 98mn bpd at present to a peak of around 104mn to 105mn. With existing capital investment having declined substantially over the past three years, it is doubtful that the global oil industry can meet this demand requirement without ramping up capital investment. As this is unlikely to happen at current prices, an eventual spike in prices at some point between now and 2020 is suggested.

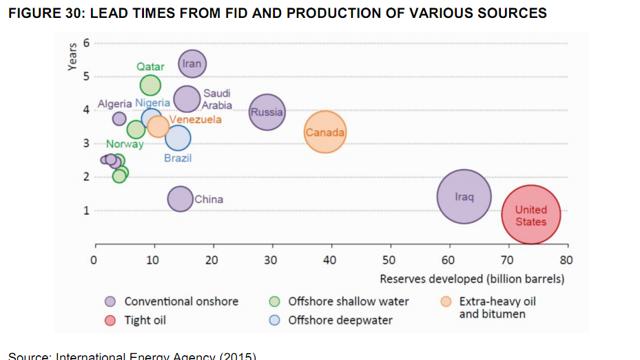

If oil prices do spike higher before 2020, it could also be argued that many oil companies may still refrain from increasing investment in new production, given the uncertainty over the timing for peak oil demand and especially if electric vehicle sales are accelerating. This is particularly true for projects with long lead times to production and heavy upfront capital expenditure requirements. The last thing any oil executive wants is to spend $5bn on a major new project that only comes on stream in say 2024, just as oil prices start to collapse as a result of rising EV penetration.

If this is the case, it could be argued that oil prices could well spike and sustain themselves at high levels of plus $80 for several years until oil demand actually peaks. The exception may well prove to be US shale companies, which have much shorter lead times to production of typically 6-9 months. They can also quickly ramp capital investment down should prices decline sharply. Given that the majority of oil produced from a typical shale well is normally produced in the first 3 years, shale companies can easily hedge out their production during periods of high oil prices and provide an additional margin of safety.

Source: International Energy Agency

Based on this competitive advantage, one may suggest that executives at major oil companies should be looking to buy up smaller US shale producers with large reserves as opposed to investing in new long lead time projects that require a large upfront capital investment. This flexibility in production could prove to be extremely valuable even in a world post 'peak oil demand'.

Consider for a moment if oil demand does peak in say 2024 and prices collapse to $25 per barrel or lower. This would devastate many traditional oil-producing nations that rely mainly on oil revenues to sustain fiscal expenditures. Countries in the Middle East would be particularly at risk and one can only imagine the potential for socioeconomic and geopolitical risk for oil prices in a sub $25 world.

The risk of supply disruptions would simply become significant as a result of the escalation in socioeconomic and geopolitical risks. It is quite possible that for several years or even a decade after peak oil demand setting in, the oil price itself could become extremely volatile. This could see trade of between $20 and $80 per barrel as periodic supply disruptions impact global energy markets. Any kind of long-term planning by the major oil companies would be impossible in this type of environment.

The ability to ramp production from shale and hedge that production at the same time, would make it possible to profitably sustain oil production, perhaps for several more years, after peak oil demand sets in. From our perspective, although the long-term outlook for oil is negative, the one investable sector of the energy market may paradoxically be the US shale industry, despite the current negative sentiment.

If you are an executive at a major global oil company, it must surely make sense to buy up shale acreage or reserves as a flexible 'buffer' against the potential disruption and volatility which global energy markets may exhibit in the next decade.

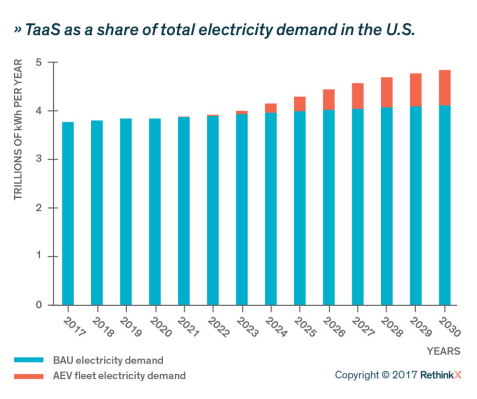

Given the spread between natural gas prices and oil prices being currently greater than the BTU conversion spread of 6x, there would also appear to be limited downside to US natural gas prices from current levels of around $3 per MCF. Unlike oil, the future of natural gas appears to be quite secure for at least a few more decades. Demand from industry in petrochemicals and fertilizers will continue to grow, while the rise or widespread use of EVs will also increase total electricity demand.

Citing the report produced by Seba and Ariba, under a scenario where 95% of passenger miles are serviced by EVs, total electricity demand would grow incrementally by 18% over current baseline EIA projections.

With coal and nuclear still accounting for 50% of total electricity generation, the increase in total electricity consumption will leave plenty of room for growth in renewables such as solar and wind and also still accommodate future growth in electricity generation from natural gas. There are vast natural gas reserves in the US, but it remains unclear what percentage is truly economically viable below $3 per MCF. If this is the case, a long-term price of $4 per MCF, or $25 per barrel for oil on a BTU equivalent basis, would prove more realistic. This is also consistent with the long-term outlook for oil prices post a peak in oil demand.

If the worst-case scenario for oil and shale oil producers proves correct, the supply of natural gas as a by-product of oil production will also collapse and further underpin the long-term demand/supply fundamentals for natural gas. This would suggest that the most attractive shale companies to invest in right now are perhaps those with mixed or diversified portfolios of both liquids and natural gas reserves. A further margin of safety is offered by those operations with very large reserves of 20 to 30 plus years at current production levels.

Even more attractive to major oil companies would be those companies with mixed liquid/gas portfolios and large reserves, but with an inability to meaningfully ramp production due to capital and/or balance sheet constraints. Given the current negative sentiment towards these companies, there are a number that tick all these boxes. There are more importantly some concerns with large, high-quality natural gas reserves that would become very valuable if we assume a long-term equilibrium natural gas price of $4 per MCF.

More importantly there are some with large companies with high quality, natural gas reserves that would become very valuable if we assume a long-term equilibrium natural gas price of $4 per MCF. And if anything, the economics of natural gas extraction in the US, over the long term, may prove to be far more economical than oil extraction on a BTU equivalent basis.

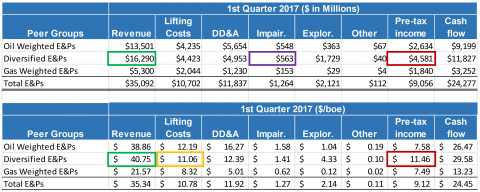

Looking at the table below from RBN Energy, it would suggest that even without a complete narrowing in the spread between natural gas and oil prices to the suggested BTU equivalent ratio (6x), at a long-term price of $4 per MCF and $50 for oil, natural gas production would prove more rewarding in terms of total return on investment.

Assuming a natural gas price of $4 per MCF or $24 per barrel on an oil-equivalent basis as well as total lifting and capital costs of $13 per barrel of oil equivalent, natural gas companies would deliver a pre-tax or EBIT margin of nearly 50%. For oil producers, assuming a long-term oil price of $50 (optimistic if the more aggressive predictions for EV penetration prove correct), the long-term EBIT margin would only amount to 40%.

Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours.

I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Source: The Rise Of Electric Vehicles - Are There Still Opportunities For Investors In The Energy Sector?

DAVID LINKLATER/FAIRFAX NZ

DAVID LINKLATER/FAIRFAX NZ  DAVID LINKLATER/FAIRFAX NZ

DAVID LINKLATER/FAIRFAX NZ  DAVID LINKLATER/FAIRFAX NZ

DAVID LINKLATER/FAIRFAX NZ  DAVID LINKLATER/FAIRFAX NZ

DAVID LINKLATER/FAIRFAX NZ  DAVID LINKLATER/FAIRFAX NZ

DAVID LINKLATER/FAIRFAX NZ  DAVID LINKLATER/FAIRFAX NZ

DAVID LINKLATER/FAIRFAX NZ